There’s a new gold standard in classic game preservation, and it’s Digital Eclipse’s aptly-named Gold Master Series. This is a studio that has long put its focus not just on porting old games to new platforms, but in really showcasing the legacy of those games and the history that surrounds them. Starting with The Making of Karateka, the Gold Master Series takes that notion a step further: less “retro game collection”, more interactive documentary.

Until now, the default mode for even the most historically-oriented game collections has been a demarcation of “the games” and “the other stuff”. You have all your games, emulated perfectly (hopefully), maybe with some extra tools to make playing the unaltered original a little more convenient. In a separate menu, you have the museum, chock full of artwork, development notes, anecdotes, and whatever other archival material the studio can get its hands on. There’s nothing wrong with that approach—indeed, making games playable as authentically as possible on modern hardware is the first and most critical step for any sort of preservation effort.

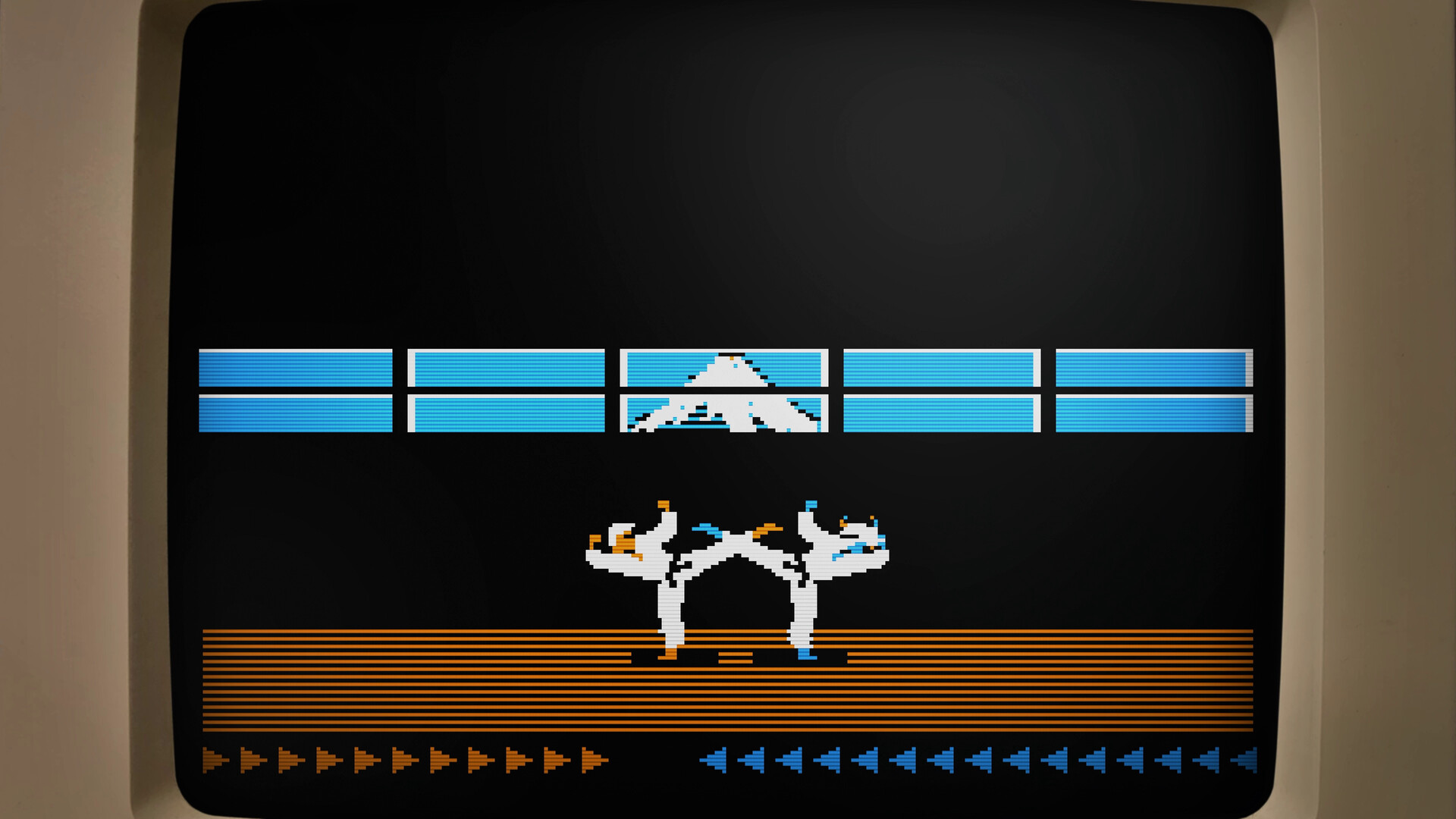

But The Making of Karateka takes a different approach. Building on the interactive timelines seen in Atari 50: The Anniversary Celebration, here you’ll find the games themselves, playable prototypes (of both Karateka and several unreleased projects that preceded it), archival material, and new interview footage grouped and organised in a narrative documentary fashion to tell the story of, well, how Jordan Mechner’s iconic Karateka came to be.

Watch a short interview clip about a particular topic, read some scanned diary entries and letters, look at some photos, play a prototype, watch another clip, play another build—so it goes, the different artifacts woven together to tell each chapter of this tale. It’s a remarkably effective way of not just putting all these different pieces into context and highlighting their relevance, but of constructing a sort of narrative history that’s more than the sum of its parts. In the more standard format, a crude prototype of a mashup of Asteroids and Breakout would be little more than a neat historical oddity that you play once and forget almost immediately, but here it becomes an essential piece of the foundation that Karateka was built upon.

The story itself is a fascinating one. An ambitious teenager gets an Apple II, teaches himself to program it, and comes close to publishing deals on several concepts that ultimately fall through. Dejected but not defeated, he finds inspiration in the storytelling Choplifter—not a plot-driven game by any means, but one whose animations, setting, objectives, and ending (“The End” rather than “Game Over”) created a sense of narrative that was unusual outside of text adventures and RPGs.

Drawing on his love of film, he comes up with the idea of a more dramatic, cinematic take on an action game, rotoscopes some video of his dad and his karate teacher doing various movements, and finds a way to program music on a computer without any kind of sound card. The result: a prototype that Doug Carlson, co-founder and then CEO of publisher Broderbund, describes as “essentially a finished game… I think he wanted to keep the whole thing under wraps and see if he could get it exactly right without any nudging or criticism.” Karateka.

It’s an intriguing insight into the way Mechner was able to realise his vision and creatively overcome technical limitations to get there, but framed in a human interest story that gives the development history weight. Karateka‘s use of rotoscoping—the first game to do so, I believe—is certainly an interesting and historically significant development anecdote. But it becomes more than that when put in the context of the relationship between Mechner and the playful, creative artists in Broderbund’s “Rubber Room” and of the unwavering support of Jordan’s father, Francis Mechner. Indeed, with much of the interview footage filmed with Jordan and Francis together, and the abundance of wonderful memories they clearly share, this father-son bond forms the backbone of The Making of Karateka as much as Karateka itself.

The documentary doesn’t stop at Karateka‘s release. It goes on to look at the game’s legacy (a fan letter from one “John Romero” is particular highlight), at the way it was marketed, and at the challenges and opportunities that came with porting to other platforms. There are some concepts for a Karateka 2 that never came to be, will certainly be familiar to anyone who’s played Mechner’s later games. The cinematic feel of Karateka but with multi-level platforming, a greater focus on exploration, and lots of deadly, devious traps? Sounds a lot like Prince of Persia…

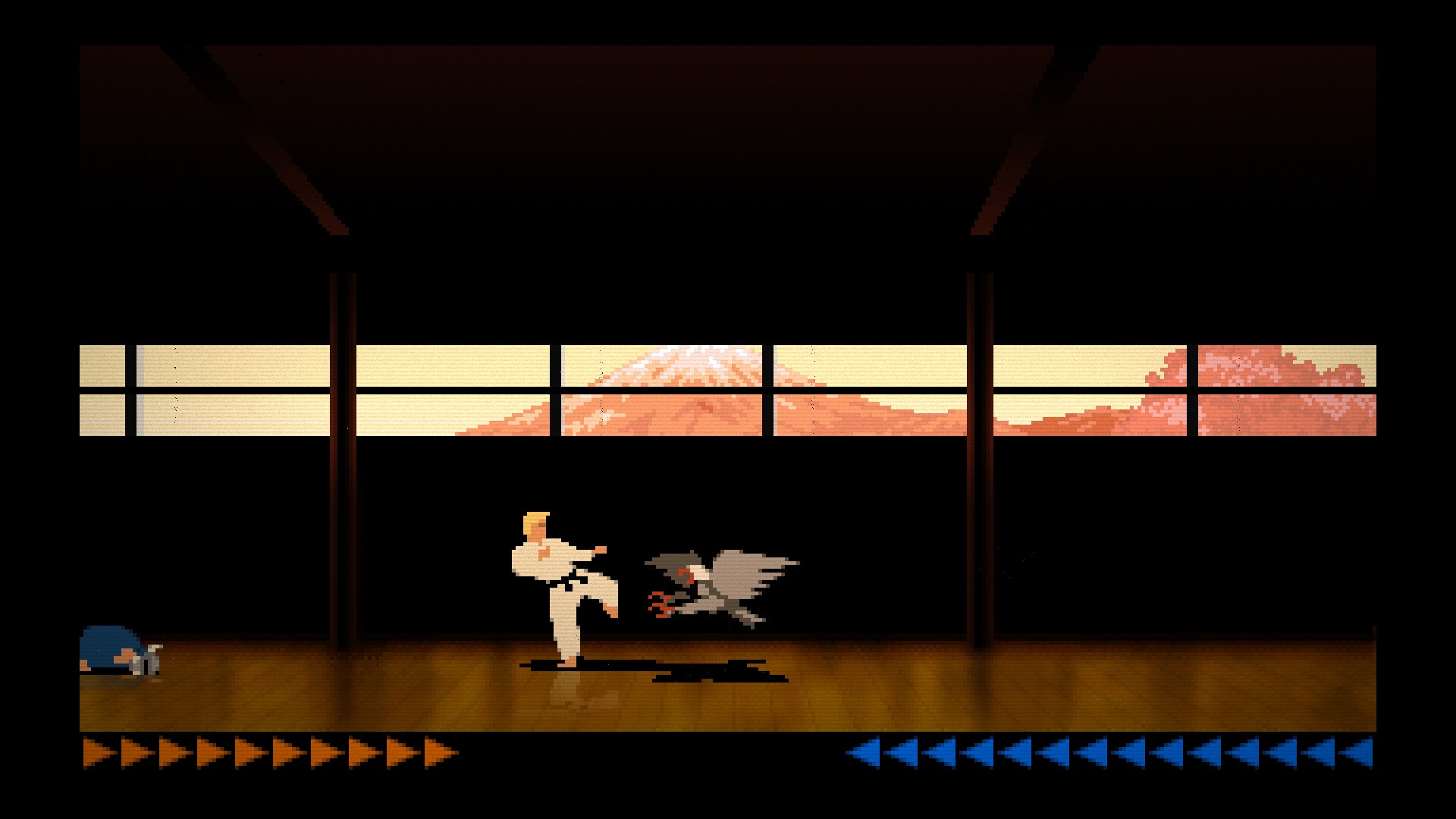

Capping it all off is Karateka Remastered. Rather than a modern take (which already exists in Liquid Entertainment’s 2012 remake), Digital Eclipse’s goal here was to create something more akin to the Amiga port of Prince of Persia: a version that can take advantage of more powerful hardware than the Apple II and realise some of the ideas that Mechner couldn’t implement in the original, while still working within a certain degree of technical limitation. The result is a sort of “modern-retro” reimagining: a graphical overhaul that channels the style of early ’90s PC games, with smoother performance and some little touches to help make the game (optionally) more approachable—namely, extra lives. Aside from one new puzzle inspired by some cut animations, the level design and overall ebb and flow are as close to the original Karateka as possible, creating a new version that feels both fresh and authentic.

Karateka Remastered is also an interesting attempt to understand why porting the original game was so challenging, and the included commentary track is a fascinating insight into the perfect balancing act in the underlying code that made Karateka work. (And for a bit of fun, there’s also Deathbounce Remastered: one of Mechner’s earlier prototypes turned into a complete game.)

I said earlier that making a game playable as authentically as possible is the most critical part of any preservation effort. That is true, but historical context and the stories that surround the game in question are a very, very, very close second. Preservation isn’t just about the game itself, but about its place in history. With its “interactive documentary” style, The Making of Karateka raises the bar for how that kind of historic legacy can be presented, preserved, and celebrated.

Few studios are as committed to celebrating video game history as Digital Eclipse. With its interactive documentary format, meticulous research, perfectly-emulated classics, playable prototypes, and a couple fantastic remasters, The Making of Karateka sets a new gold standard.