Labyrinth of Zangetsu is a great example of how, with a strong vision and a creative approach, you can do so much with comparatively little. This is a game that’s clearly been made on a modest budget—that’s not a criticism, by the way. But with a cohesive sense of style and theme, it ends up being far more visually arresting than the vast majority of big-budget blockbusters caught up in the high-fidelity arms race. A handful of striking hand-painted character and enemy portraits, some technically simple but very atmospheric environmental models, and the tension of a Wizardry-style dungeon crawler is enough to make an extremely compelling game.

Taking inspiration from yōkai stories and sumi-e painting, Labyrinth of Zangetsu envisions an Edo-period Japan beset by the “Ink of Ruin”. This plague corrupts everyone and everything it touches, turning the land outside Ido Castle—humanity’s last bastion of hope—into an ink-drenched hellscape rife with monsters. The fight to push back the ink rests on the shoulders of warriors with nothing left to lose, conscripted by the shogunate to stop the corruption’s spread.

You can see how that kind of setup brings all the pieces of Labyrinth of Zangetsu together. The inkwash portraits of the monsters you encounter create a far more ominous presence than something more colorful would, and the labyrinths, drenched as they are in murky blackness, feel alien and dangerous—a sensation that’s only enhanced by the lack of technical definition in the environmental details. It’s not entirely black and white, but the use of colour is used sparingly to create impact. Character portraits, though still in that sumi-e style, are a bit more colorful to draw the contrast between your party and the hostile world around them, while while occasional flecks of colour—red blood splatters, orange lava—punctuate monotone dungeons to signal danger, potential rewards, or both.

On top of that, it’s a visual style that just looks gorgeous on its own merits. The painterly finish bestows a sense of personality and artistry that makes every new foe you encounter stand out and feel significant, and makes the conscripts your party—unanimated and unscripted though they might be—feel like living individuals you can invest in. The tension when a character dies, to potentially be lost forever, runs high, and not just because of the time spent leveling them up.

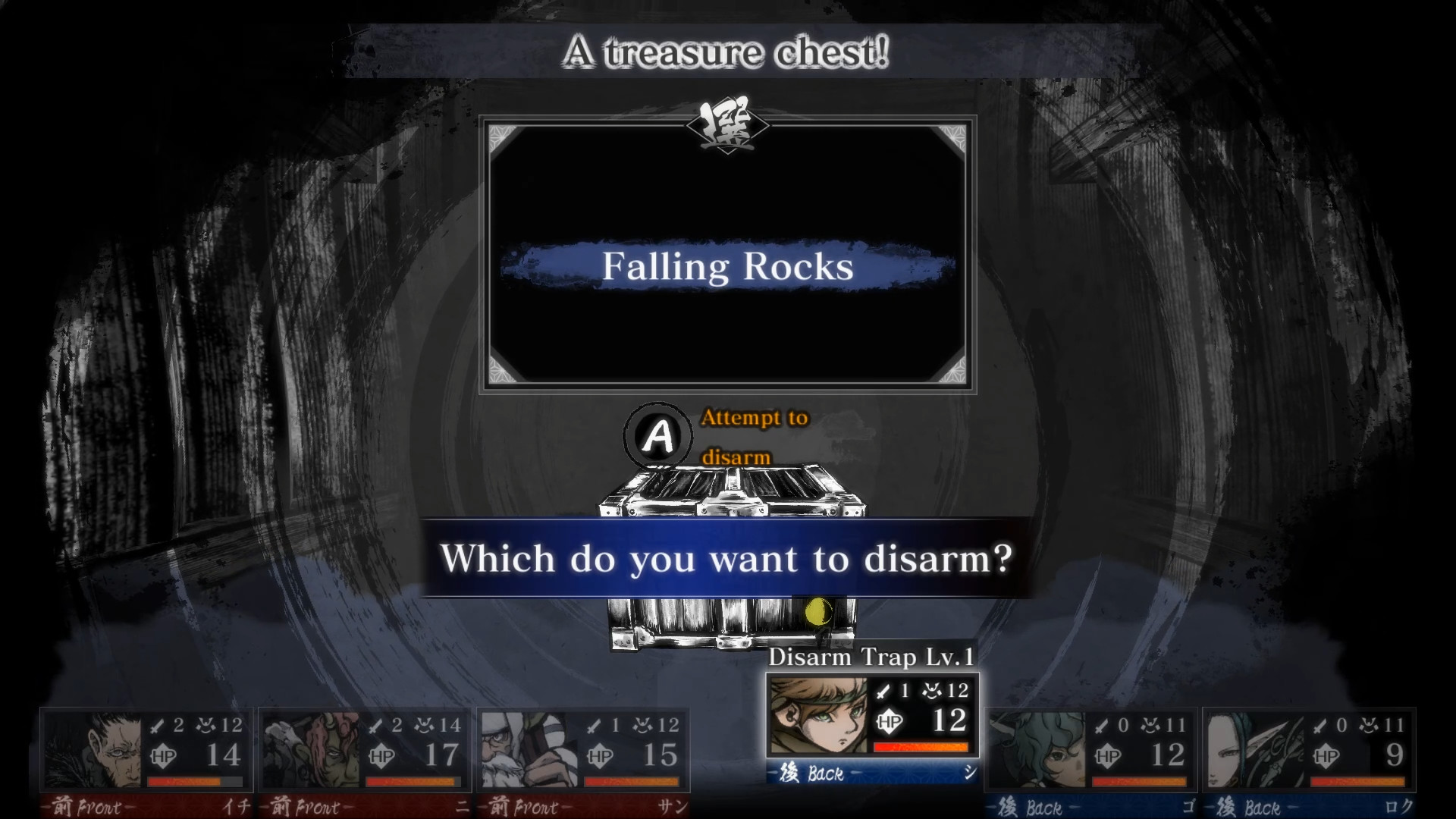

Which brings me to the game at the core of Labyrinth of Zangetsu: a classically-styled dungeon crawler where fans of Wizardry (or Etrian Odyssey, or {more recent example}—pick your point of reference) will feel right at home. The labyrinthine nature of the dungeons makes meticulous cartography both crucial and satisfying, while various traps and obstacles do everything to disorient and misdirect you. Even in an age where automapping has become standard, Zangetsu still manages to throw some devious traps in that make it hard to tell where exactly you are or which direction you’re facing. The level designers clearly had a lot of fun laying out these mazes, and that shows in just how rewarding they are to solve—and that, really, is the highlight of any game like this.

Turn-based battles break up that exploration and add another layer of tension and danger. The combat system is admittedly rudimentary, but nonetheless requires careful management of risk/reward and limited resources lest you back yourself into a corner. True to its inspirations, bad judgment and bad luck can be costly in Labyrinth of Zangetsu, and greed and carelessness can get harshly punished.

But while it can be unforgiving, Zangetsu rarely feels overwhelming—especially compared to the kind of brutality its inspirations are known for. You can almost always bounce back from a bad roll of the dice, and frequent autosaves make save scumming a viable option. Reviving fallen characters and cleansing corruption is costly at first, but by the time you get to the second dungeon, money is plentiful and has little use for much else. Even the rare situation of a resurrection failing and a character being lost forever is more of an emotional punishment than a mechanical one, with replacements able to be power-levelled fairly quickly.

This does all change if you decide to play on “hardcore” difficulty, though, where enemies are much stronger and a far more stringent save system makes scumming less of an option. For the people who cut their teeth on Wizardry of old and want a similarly dangerous adventure, hardcore mode is the way to go.

While Labyrinth of Zangetsu does a lot with a little, it can suffer from its limited scope at times, too. It’s a relatively brief outing, as dungeon crawlers go, which isn’t inherently a bad thing—as a time-poor parent, I appreciate the brevity—but it also means that the game struggles to push its ideas to their full potential. Even with a variety of classes and the option to multiclass, their rudimentary designs can limit options for creative character and party builds. Labyrinth designs are consistently great, but it still feels like there’s untapped potential in the various gimmicks and traps that the game introduces.

But as I’d like to see Labyrinth of Zangetsu push those limits a little more, “more” costs money—and I’d never want to see a game like this trade style and identity for scope. Acquire’s priorities were spot on here, turning limited resources into something unique, visually arresting, and a whole lot of fun. That’s more than I can say for most multi-million dollar blockbusters.

Labyrinth of Zangetsu proves how far a strong vision and creative approach can go, even with—or perhaps in spite of—a limited budget.